- Inside the Smelter Catastrophe

- Scenes at the Hospital

- A Story of Pain, From Indonesia to China

- A Trail of Injuries and Deaths

- Caught Under the National Project Shadows

- The Invisible Struggles

Flames

of Death

Flames of Death

Unveiling the nickel’s industry grim reality

Written and coordinated by Febriana Firdaus (full credit list below)

Published on Nov 18, 2024

Irwandi, a worker at PT Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP), uploaded a video on the WeChat messaging application about ongoing repairs at the ferrosilicon smelter building.

It was a day before Christmas in 2023, but smelters in the building, owned by PT Indonesia Tsingshan Stainless Steel (ITSS), ran like clockwork.

In the video, workers can be seen doing welding work to fix a furnace. Sparks fly, like a firework.

Irwandi’s post showed several oxygen tanks lined up for welding. He uploaded the video at 1:04 a.m., and a friend commented on it.

Irwandi continued to post three more videos. His last post was at 5:32 a.m., 40 minutes before the explosion.

The blast killed 21 workers and injured dozens of others, local media reported. Of the deceased, 13 were Indonesian citizens and eight were Chinese nationals.

Irwandi was one of those who died on the spot.

IMIP is a 4,000-hectare industrial complex in Bahadopi district, Morowali regency, in Indonesia’s Central Sulawesi province.

Known as the world’s largest nickel industrial zone, IMIP employs more than 80,000 workers, not including 19,000 infrastructure project workers.

Most workers come from communities across Sulawesi and nearby eastern islands of Indonesia. Some are recruited by IMIP as permanent employees, and some as temporary workers through subcontractors.

IMIP is designed to process and refine nickel ore. The site has not only 55 tenants that process ore into nickel, stainless steel, and carbon steel, but also a seaport, airport, hospital, power plant, religious facilities, and housing for workers.

Nickel, a metallic element, is used to make rechargeable batteries for products like electric vehicles (EVs). As the push for green technology accelerates worldwide, the demand for nickel has also risen.

Indonesia is currently the world’s largest nickel producer. It is projected to mine 62% and refine 44% of global supply in 2030, according to the International Energy Agency's Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024 report. Other major players are the Philippines, which mines 8% of global nickel supply, and China refining 21%.

According to the Minor Metals Trade Association, IMIP’s production supports Indonesia’s goal of supplying over 30% of the world's nickel for stainless steel and EV battery markets.

The nature of the supply chain has revealed health and safety hazards affecting the most vulnerable – workers on the ground.

This concern is particularly acute in Indonesia, where nickel deposits primarily consist of lateritic nickel, which has a lower nickel content compared with sulfide nickel.

The processing of lateritic nickel is complex and energy-intensive, requiring the High-Pressure Acid Leaching process. As demand for high-purity nickel, especially for EV batteries, continues to rise, the associated risks from its chemical reactions remain significant.

Inside the Smelter Catastrophe

The Environmental Reporting Collective interviewed some survivors of the December 2023 explosion to investigate the chaos inside the accident and unveil the grim reality of working in the world’s largest nickel industrial zone.

The interviews were conducted while the survivors were still treated in hospital and before the company approached them and their families. We gave three of them pseudonyms Atu, Akko, and Elon to protect their safety.

On the morning of Dec. 24, Atu, who worked in the kiln section of the building, witnessed the horrifying scene of workers fleeing.

The CCTV video from different directions shows the footage of the explosion.

He arrived at IMIP early to begin his workday. He was about 50 m from the incident site and walking toward the building when a loud explosion reverberated through the camp.

“I ran (toward the building) because many colleagues were there,” he tells ERC. “I saw many people jumping, many were raising their hands asking for help. But we, their colleagues, couldn’t do anything because we didn’t have the tools to save them.”

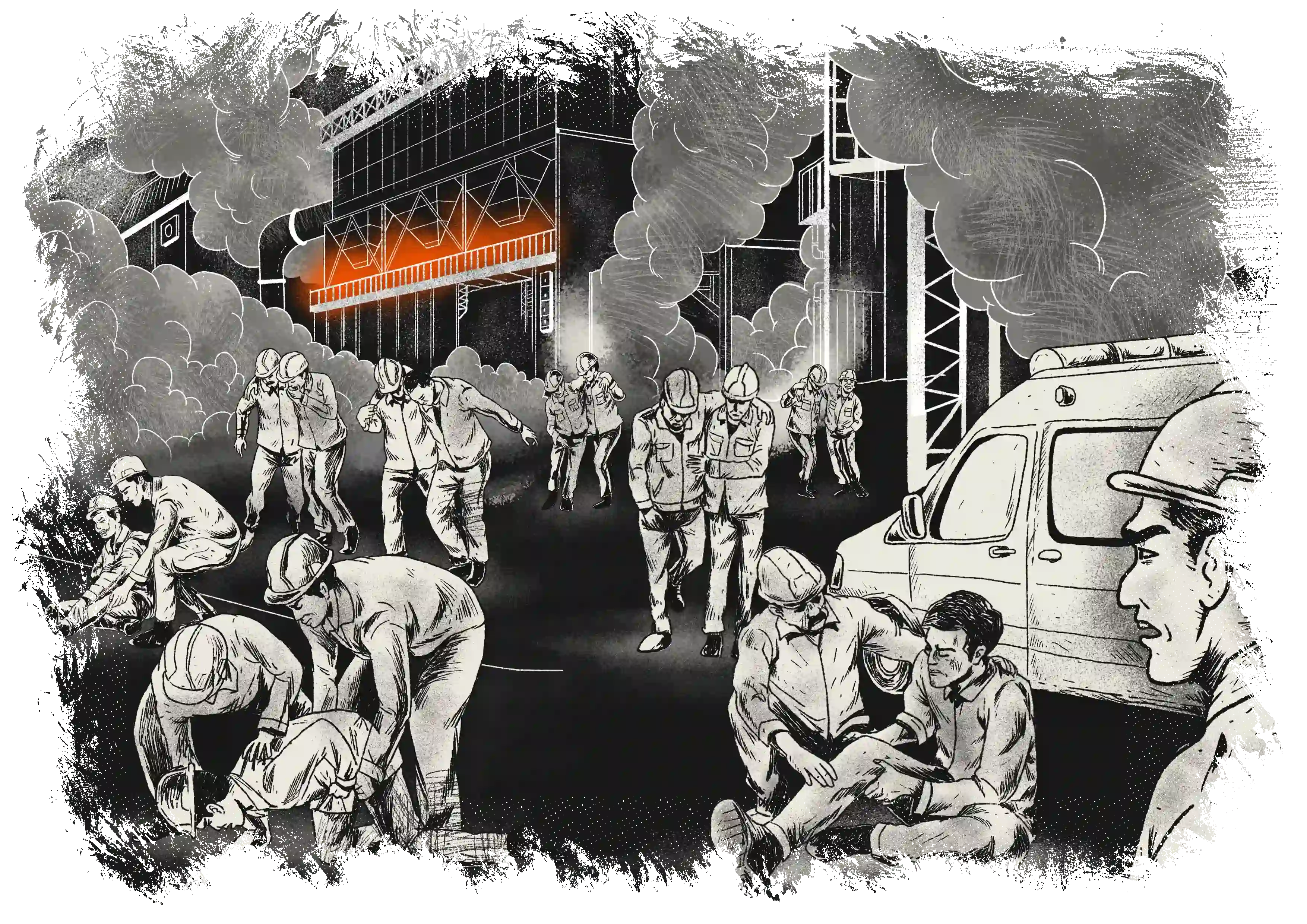

As chaos erupted, Atu described the scene as frightening and overwhelming. “I saw people running, some in panic. Smoke was rising fast, and everyone just wanted to get out of there,” he says.

He tried helping friends who jumped off the building from the upper floors. “Some of the individuals were already burned,” he said.

The IMIP clinic was about 1 km from the explosion site, and it took about 15 minutes for the ambulance to arrive. In the meantime, Atu and his colleagues used a company patrol car to evacuate many workers. They also stopped other vehicles to transport injured colleagues.

“Some were loaded into a pickup truck. We tried our best to ensure all the affected friends who were suffering were taken care of, and some were unconscious,” he says.

Atu recalls seeing a Chinese and an Indonesian worker standing on the roof of a fifth-floor building, attempting to escape. The Indonesian man could climb down a pipe, but the Chinese worker “forced himself to jump and then he passed out,” he says. Atu took the Chinese man to the clinic, but he later died.

Firefighters arrived around 15 minutes later but struggled to control the growing blaze, he adds. Later, security and emergency services arrived to bring some order to the situation.

On the day of the incident, Akko arrived to work on the third floor of the multi-story furnace where the electrical system controlling the furnace’s power was located.

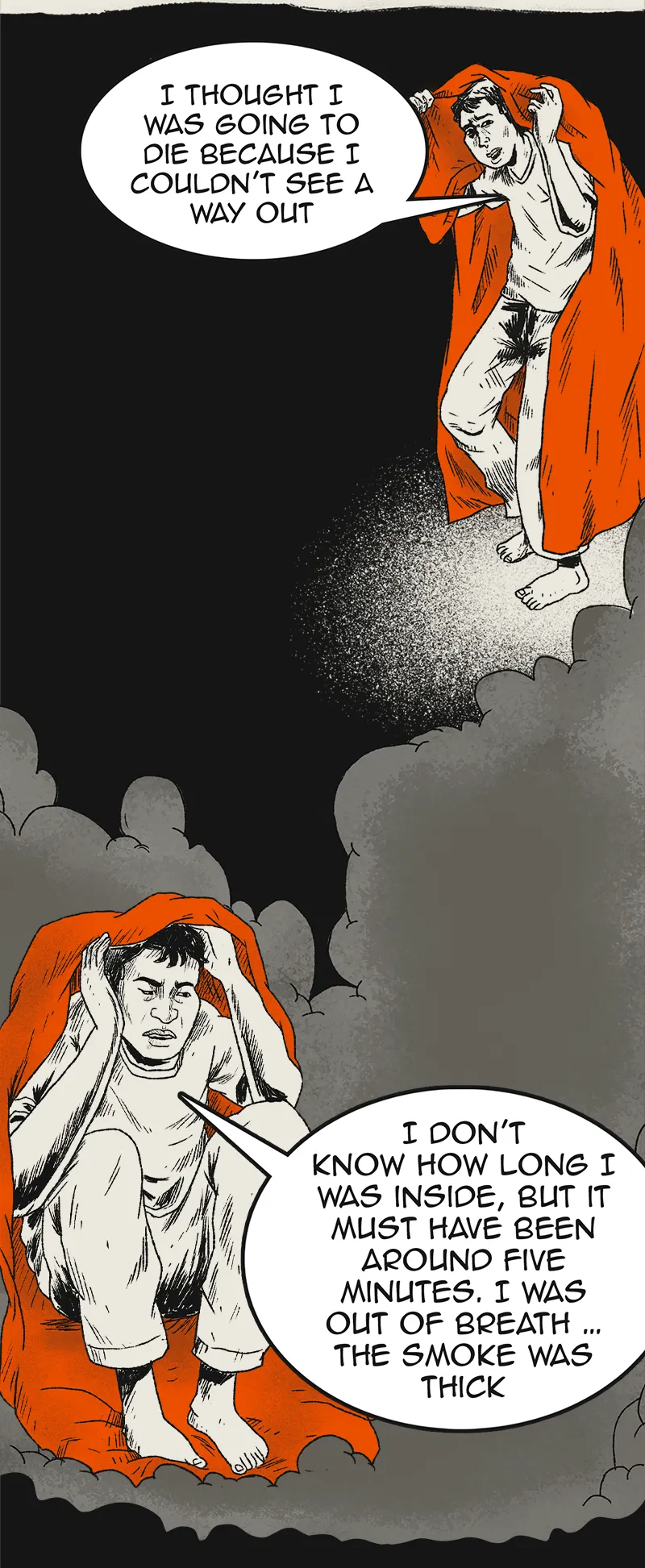

He arrived at the rest area at 6 a.m. and was preparing for his shift when the explosion happened. “I just made coffee,” he says. He had not put on his personal protective equipment (PPE) – he was barefoot and just wearing a T-shirt.

The rest area was filled with workers when suddenly, a loud explosion rocked the building.

Without time to think, Akko ran frantically, unsure where to go.

In the chaos, he wrapped himself in insulating material, hoping it would protect him. “I used an orange, somewhat thick, insulating carpet – not for cables, but for the floor – to protect myself from electric shock.”

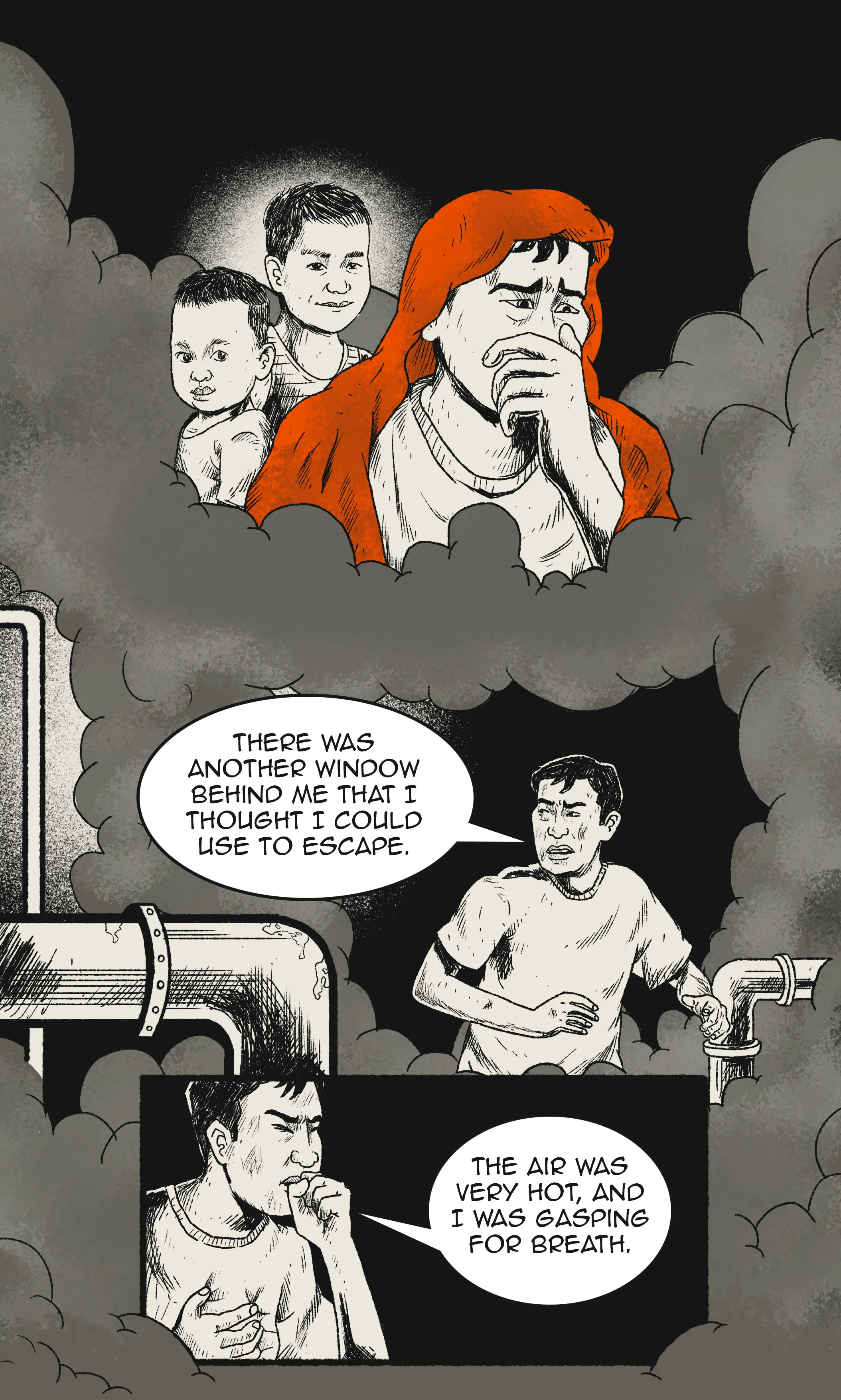

Akko sat alone in a small room with the lights out as the smoke thickened and the temperature rose, making it harder for him to breathe.

undefined

undefined

In the dark, he remembered his family. “I said, It’s not good to die like this. I remembered everything, my wife, my child.”

He started searching for a way out.

undefined

undefined

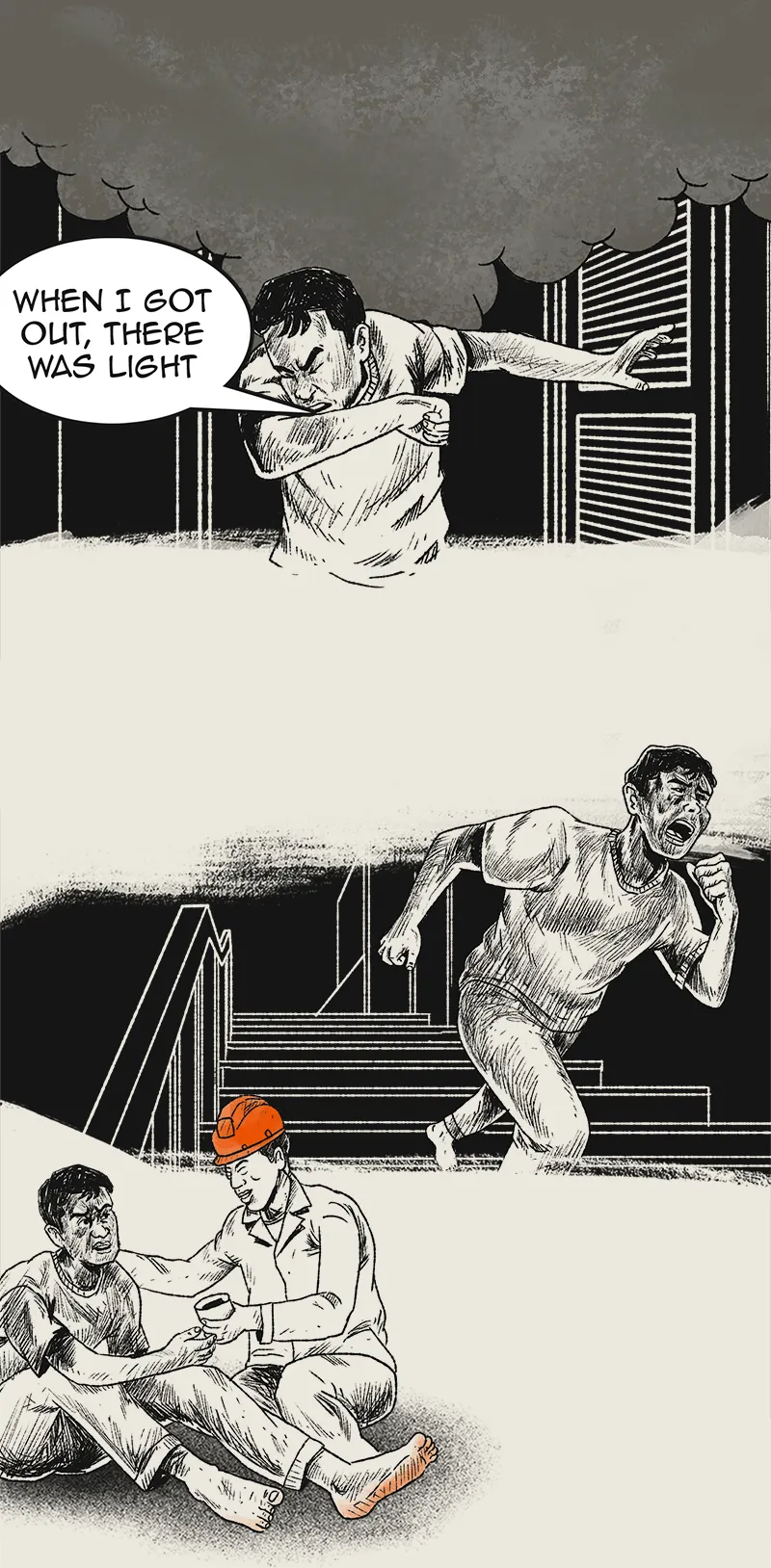

Finally, he was able to open the window and jump down from the third floor.

By the time he emerged, his body was blackened, covered in dust and smoke, his hair was slightly burned, and his face was unrecognizable.

When he reached safety, a Chinese worker gave him water. He was then taken to the clinic for treatment.

undefined

Akko also tells ERC that the fire blocked and engulfed the emergency exits, forcing many workers to jump out of the building and causing broken bones. “While the [escape] routes were technically available, they were too dangerous to use,” he says.

Elon, Akko’s colleague, was also trapped on the third floor when the furnace exploded. It caused panic and filled the building with thick smoke. Struggling to breathe and being unable to see, Elon could only hear cries and screams from his trapped co-workers. As he walked and felt along the walls and railings, his hands and face began to blister from the heat.

Elon found an escape route when he saw a metal pipe leading to the ground floor. However, after sliding just a few meters, the intense heat forced him to release his grip, causing him to fall onto another worker clinging to a railing on the second floor. Together, they plummeted to the ground floor, landing among other injured workers.

Despite the pain, Elon managed to stagger to his feet. He noticed other workers lying, either silently or groaning. He was later taken to the IMIP clinic for treatment.

Scenes at the Hospital

At 8:10 a.m., on-duty health care workers at Morowali Regional General Hospital were supposed to be replaced by the next shift. However, they had to stay on after the hospital received a continuous stream of ambulances bringing blast victims.

The ITSS smelter is 29 km, or 47 minutes, away from the hospital. It took 12 hours to evacuate around 30 casualties from the smelter fire.

During this time, ambulance sirens blared continuously, causing panic among other patients. Some of their family members documented the scenes of victims being brought into the Emergency Room (ER).

The ER, equipped with only 17 beds, could not accommodate all the victims, leaving some lying on the floor. One injured patient, with burns on his back, had to lie face down on the floor.

Some also had broken bones and head injuries. The smell of burnt flesh quickly filled the ER.

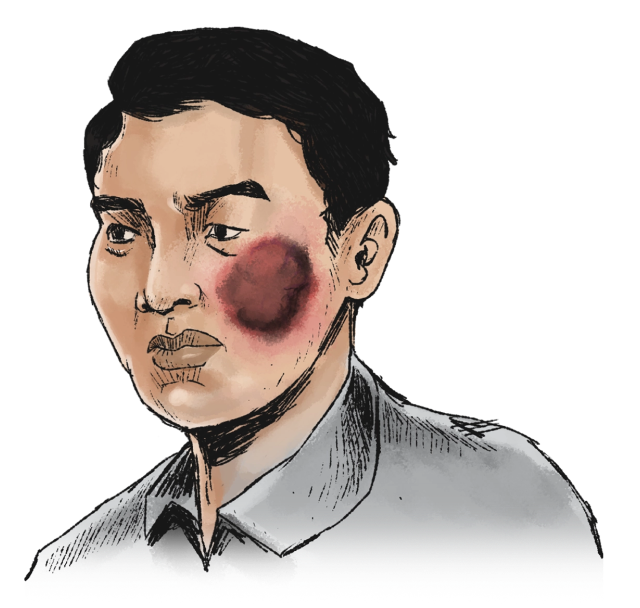

Nopi Pasea, a 24-year-old ITSS worker who suffered second-degree burns, was first treated in the ER and later transferred to a VIP room, where he was accompanied by his older sister and mother. When ERC interviewed him, his right leg was put in a splint and wrapped in gauze, and his right shoulder was in a sling due to dislocation.

Nopi says he was about to end his shift at 5 a.m. when a colleague asked him to help fix a furnace. When they cut and opened it, the equipment suddenly caught fire and exploded. The workers ran everywhere in panic. There was one emergency staircase but it was engulfed in flames. “We had no choice but to jump from a height of 12 m,” Nopi says.

After the interview, Nopi cannot be contacted anymore.

ERC reached out to other victims, but they also declined to speak. It is believed IMIP instructed them not to discuss the Dec. 24 explosion with the media.

Degree of burns

First-degree burns

Affect the epidermis/outermost layer of skin and usually heal within 5-7 days.

Second-degree burns

Second-degree A (superficial):Damage affects the superficial/epidermis and upper dermis (the middle skin layer between the epidermis and subcutaneous tissue) and heals within 10-14 days. Second-degree B (deep): Damage affects almost the entire dermis layer.

Third-degree burns

Damage affects the entire dermis or the innermost skin layer (subcutaneous tissue), and healing takes a long time due to the lack of epithelialization (regeneration of the epidermis to cover the wound).

The 21 workers lost their lives after being treated for serious injuries, primarily burns and head trauma sustained from jumping from a higher floor.

ERC obtained triage records of the explosion victims treated at Morowali Regional Hospital, which showed that they sustained second-degree burn injuries.

We showed the triage records to Prof. Dr. Faisal Yunus, an expert council member at the Indonesian Medical Association for Occupational Health (IDKI).

Faisal says external burns affected 70%-80% of their bodies. Inhaling hot air and smoke also affected their internal organs, causing airways to narrow and leading to edema, or swelling caused by fluid accumulation. It also had effects on the throat and the lungs, making it difficult for them to breathe.

“The severe injuries and deaths of the victims indicated that the fire was intense. It burned for a long time, and the victims inhaled the smoke and were exposed to heat for an extended period,” Faisal says.

In an email to ERC, Morowali Regional Hospital says that they treated 30 patients from the December 2023 explosion at IMIP, with more than 26% suffering from severe burn injuries and over 73% light to moderate burn injuries.

A Story of Pain, From Indonesia to China

In a remote village in Sulawesi, Elon’s mother had just finished her chores on the morning of Dec. 24 when her mobile phone rang repeatedly. The calls were from an unknown number, and upon answering, she received devastating news: her son had been involved in a work accident.

She immediately headed to Makassar Airport and purchased a ticket to Morowali, which was about 380 km away. Upon arrival, Elon’s friends picked her up at Maleo Airport and took her to the IMIP clinic in Bahadopi.

When she saw her son, her heart sank, and she cried in anguish. Due to Elon’s severe burn injuries, he was transferred to Morowali Regional Hospital on Christmas Day.

IMIP representatives gave a compensation of IDR 3 million, around USD 190, to Elon on Dec. 26. That same day, he was transferred to another hospital. In late January 2024, he underwent surgery, and his condition started to improve. When ERC talked with him on Jan. 31, his arms and thighs were still bandaged, leaving only the tips of his blackened fingers visible, and all her fingernails had fallen off.

Elon, who earned a maximum wage of IDR 8 million per month, received daily visits from IMIP representatives, who sometimes brought food and fruit. “That was the only time the company gave him IDR 3 million,” his mother laments. “After that, there was nothing more.”

She also says when Elon underwent surgery, some medications were not covered by BPJS Kesehatan, Indonesia’s health insurance program. “We had to purchase [the medicine] ourselves and ended up spending IDR 2 million,” the mother says.

IMIP told Indonesian media that it compensated the family of each deceased worker IDR 600 million, or nearly USD 40,000.

Li Hongjun (李红俊) was one of the eight Chinese workers lost their lives following the December 2023 blast. ERC visited his family in Pei village, Wenxi county, China’s Shanxi province, in June 2024.

Li’s mother is taken aback when she hears the details of the IMIP explosions and the accidents involving Chinese workers in Sulawesi. She is silent at first, then shakes her head and says: “I don’t care about compensation; I don’t want to know about it. He is gone.”

Li’s father says IMIP paid them compensation of approximately RMB 1 million, or nearly USD 14,000 – similar to the compensation given to steel factory workers who fall victim to occupational accidents in China. It was enough to support the family for a while: taking care of the needs of Li's widow, his parents, and his son’s education.

“I don't know how much compensation was paid for Indonesian workers who died,” Li’s father says. “I heard the compensation was much less than ours, because Indonesia's economic conditions are worse. The wages of workers in Indonesia are also lower than those of Chinese workers."

In Pei village, factory work is a familiar path for many young people, allowing them to earn between RMB 5,000 to RMB 8,000 per month. Li was no exception.

In 2021, an IMIP subsidiary company held a job fair in Wenxi county. Most people expressed no interest, but some, including Li, were attracted by the higher pay and decided to seek opportunities in Indonesia.

Tragically, Li was among the Chinese workers who lost their lives in workplace accidents in Indonesia.

As countries around the world strive to reduce their carbon footprint and transition to more sustainable forms of energy, there is a hidden price to green technology. For some people, they pay with their lives.

A Trail of Injuries and Deaths

Indonesia is known as the country with the largest nickel reserves and nickel ore production. Mobile phones, laptops, cameras, and electric vehicles all rely on rechargeable batteries that contain nickel.

However, accidents seem to persist in the race to supply precious metals and minerals to meet production targets, and demand, for green technology.

Just four days after the explosions at ITSS, a fire broke out at PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry (GNI) in East Petasia district, North Morowali regency. The fire started just before 5 p.m. as workers were preparing to end their shifts or transition to new ones.

Smelter II at GNI, an older facility compared with those at ITSS, has a history of frequent breakdowns, including two fires in January and July 2023, which resulted in three fatalities.

Accidents continued to occur. On June 13, 2024, an incident at IMIP injured two workers, sending them to intensive care. It occurred in the same area as the December 2023 explosions that killed 21.

IMIP confirmed the June incident but denied it was an explosion.

Trend Asia, an Indonesian NGO focused on energy transition, has been monitoring news about workplace accidents in Indonesian smelters. They documented 114 incidents at smelters in Sulawesi and Maluku from 2015 to 2023, causing 101 fatalities and 240 injuries.

Their investigation also highlighted the nickel industrial sites with the highest deaths, with IMIP topping the list. In the first half of 2024 alone, there were eight fatalities and 63 injuries there.

Ahmad Ashov Birry, Trend Asia’s program director, says workers are forced to work overtime to earn additional income, sometimes working double shifts. Fatigue becomes an additional risk factor, increasing the risks of potentially fatal accidents.

Ashov points out that the companies do not take responsibility for occupational health and safety. For instance, the personal protective equipments (PPEs) provided to workers are often “not adequate or suited to the risks, such as heat exposure or chemical exposure.”

“Different grades of PPEs are needed based on specific risk levels, but we found that PPEs are often self-provided rather than employer-provided,” he says.

Workers tell ERC that the PPEs from the companies are often of poor quality, limited in supply, and not replaced when damaged. They complain that they are given thin and incomplete protective gear, and other similar deficiencies, and they face delays in replacing mask filters.

”There is so much dust inside, we can barely see each other,” says Keteng, a worker at IMIP. “The masks are practically useless because they are only given out in limited numbers.”

Workers say they often have to keep using their damaged masks.

Gatta, an employee at the GNI smelter, says he frequently breathes in dusty air, which causes shortness of breath. The dust also irritates and stings his eyes, which requires him to wear protective goggles.

However, those who need them have to make a request and approval often takes at least a week.

During a visit to Morowali, ERC saw numerous PPE vendors around the area, further indicating that workers need to purchase their own gear.

The four biggest industrial sites – IMIP, PT Virtue Dragon Nickel Industry (VDNI), PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry (GNI) and PT Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) – also have the highest fatalities, Trend Asia’s data shows.

Our investigation also found IMIP ambulances transported at least 333 patients to Morowali Regional General Hospital throughout 2023.

According to Faisal from IDKI, the most common cases among workers include bone fractures, burn injuries, and respiratory infections.

“Bone fractures are prevalent,” he says. “These can result from falls or contacts with tools, especially in dark, wet environments where slipping is a risk.

“Workers in mines are exposed to fire hazards during tasks like welding. The use of certain liquids or gasses in confined spaces increases the risk of burns.

“Factors such as poor sanitation, long work hours, inadequate rest, poor nutrition, and insufficient protective equipment contribute to respiratory issues, including pneumonia and tuberculosis (TB).

“In mines, these risks are heightened by poor air circulation and the presence of bacteria, viruses, or fungi.”

According to data from Morowali Regional Hospital, its emergency department treated a total number of 253 IMIP cases in 2023.

“Most of the patients from IMIP were treated for work-related accidents, such as fractures, respiratory infections, and burns,” the hospital tells ERC. “However, some were also treated for other illnesses, such as diarrhea, dengue fever, and other conditions.”

In January 2024 alone, the emergency department treated 97 IMIP cases, Morowali Regional Hospital says.

A former staff member at the IMIP clinic tells ERC about frequent, often fatal workplace accidents. While employees receive annual medical check-ups, foreign workers who die are cremated, and their ashes are sent home. Videos about accidents at IMIP trigger responses from the company’s cyber team to suppress information.

ERC interviewed 52 workers from the four industrial sites on their working conditions.

Workers say they have raised concerns about workplace safety conditions to their employers but some are hesitant to report accidents due to fear of repercussions.

Meanwhile, workers at the four companies say they have to contend with deadly road conditions just to get to work.

A worker at VDNI says road accidents are common, many involving dump trucks. “In a month, there are three to four accidents, including fatalities from being run over by dump trucks,” she says. “There have been many accidents due to poor lighting and roads that are unsuitable for motor vehicles.”

Another worker concurs. “Unfit vehicles are still being used, leading to frequent tire blowouts, loss of control, and accidents like trucks veering off the hauling road or overturning,” he says. “Sometimes drivers, exhausted from 12-hour shifts, doze off behind the wheel and crash into other vehicles.”

Workers are not safe indoors, either. They are exposed to occupational hazards due to extremely unsafe work conditions. Workers endure a range of injuries, from blackened nails due to fingers caught in machines, to severe burns from splashes of molten ore.

Daily accidents could escalate into larger, more serious incidents, In one incident witnessed by a GNI worker called Eka, a small flame became much bigger after employees mistakenly threw oil into the fire, thinking it was water.

In his three years working at GNI, Eka noticed that while such incidents were rare, the rapid spread of the fire was alarming. Site supervisors could not do much because of the language barrier: they mainly spoke Chinese while the workers spoke Indonesian. It compounded the difficulties in controlling an emergency situation.

Surya works on the sixth floor of the IMIP smelter, where conditions are sweltering hot and saturated with thick smoke and steam. Despite the harsh environment, he only wears basic PPE that lacks heat resistance, consisting of only a mask, a helmet, and a pair of safety shoes.

He almost lost his life when he tried to save a fellow worker.

“Once, during production at the skimming stage, a dense cloud of smoke enveloped the area. One of my colleagues failed to descend from the hoist crane in the slag zone,” Surya says.

“He radioed in, informing us that he was on the verge of fainting, and then he lost consciousness. We rushed to rescue him, but we didn’t have heat-resistant PPE – our gloves melted while attempting to pull him out. We relied solely on air spray (APAR) to help extract him.”

Surya was gasping for air as he tried to save his colleague. He could have easily lost his life, but he persevered. Fortunately, he could save his friend and he himself emerged unscathed.

Dabir works in the molding section of PT Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP), in Halmahera, North Maluku province. He too faces occupational hazards – molten metal often splashes onto his hands and feet – but his protective gear is insufficient. Small explosions occur frequently, sometimes as often as three times a week, due to excess water in the furnace.

“When there’s an explosion, I run and hide as far away as possible,” Dabir says.

When contacted by ERC, IMIP refutes the workers’ allegations, saying the company complies with labor regulations, including reporting all workplace accidents to relevant authorities, ensuring employees receive benefits, providing enough PPEs and ensuring working hours are in accordance with labor laws.

At the time of publication, the other three companies – VDNI, GNI and IWIP – have not responded to our requests for comments.

Caught Under the National Project Shadows

In the December 2023 explosions, two Chinese nationals – supervisors at PT Zhao Hui Nikel and PT Ocean Sky Metal Indonesia – were charged with negligence of safety protocols.

Luhut Binsar Panjaitan, then Indonesian coordinating minister for maritime affairs and investment, blamed ITSS nickel smelter for violating Standard Operating Procedures, which he said, contributed to the blasts.

Despite the substantial presence of Chinese investors, Beijing has largely remained silent. The Chinese embassy provided limited information – and assistance only to the company – after the fatal explosions.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Labor, citing NGO reports, said that nickel-processing facilities in Central and South Sulawesi provinces – the majority of which are owned by Chinese companies – employ Chinese nationals as forced labor.

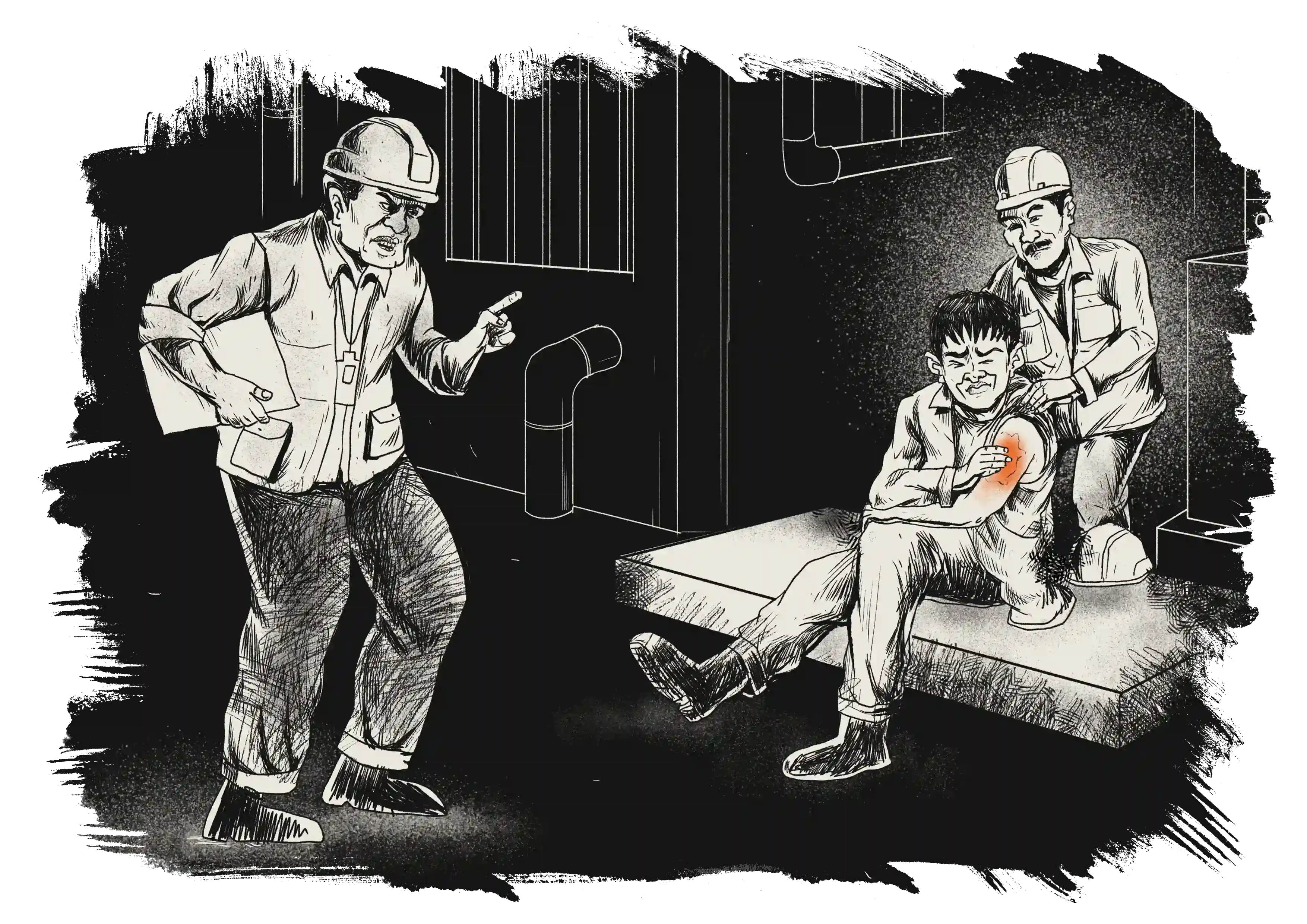

“Workers are often deceptively recruited in China,” the U.S. government report says. “After they arrive in Indonesia, many workers receive a lower wage than promised along with longer work hours. Workers regularly have passports confiscated by employers and experience arbitrary deduction of wages, as well as physical and verbal violence as means of punishment.”

Environmental activists frequently criticize inadequate law enforcement and lack of regular occupational health and safety (OHS) monitoring by the companies and the Indonesian Ministry of Manpower.

Activist Melky Nahar from the Network for Mining Advocacy (Jatam) opined that frequent accidents in the nickel industry stem from two primary issues: companies’ neglect of their occupational hazard and safety (OHS) obligations and inadequate regular monitoring by the companies and the Ministry of Manpower.

Melky pointed out that inspections are rare, typically occurring only after accidents. He added that rather than imposing substantial penalties, companies are simply advised to comply with OHS standards.

This inconsistent enforcement of safety regulations, Melky warns, creates a hazardous environment where accidents persist. “It’s like a time bomb waiting to go off.”

Nickel industrial areas are part of Indonesia’s National Strategic Projects.

Officially established in 2016 by then President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, the strategic projects encompass various sectors, from transport infrastructures and industrial zones to energy and tourism, among others. The government claims the strategic projects could boost economic growth and enhance community welfare.

The projects get priorities from the government and benefit from privileges, such as streamlined regulatory approvals and fast-tracked land acquisitions.

However, Ashov of Trend Asia points out there is no effective oversight of the National Strategic Projects. “The accountability framework is unclear, making it difficult to determine responsibility,” he says. “This lack of transparency appears to sidestep existing laws.”

In addition, Ashov notes, “We have flagged the recurring fatalities without seeing any substantial improvements.” He adds that they have questioned the Ministry of Manpower on its actions and reached out to the Coordinating Ministry for Maritime Affairs and Investment – all without any reply so far.

IMIP has been designated not only as a National Strategic Project but also as a National Vital Object, enjoying special security protections from the Indonesian police. But the designation only exacerbates the situation.

Airlangga Julio, a lawyer at Jakarta-based AMAR Law Firm & Public Interest Law Office, frequently represents local and migrant workers facing labor rights violations in Indonesia’s nickel industry.

He says that over the past one to two years, there have been multiple explosions and fires at nickel smelters, sometimes within the same company. However, it has been difficult for journalists, NGOs and lawyers to investigate the incidents.

He believes that the National Vital Object status allows nickel smelters to isolate and limit access to industrial areas, and to closely monitor people and goods entering and exiting the sites. “There are strict regulations on who can enter and who cannot, and access is also limited,” Airlangga says.

Meanwhile, many work accidents may go unreported, as incidents are often quickly classified as workers’ negligence or failures rather than being recognized as work accidents. Airlangga points out that in Morowali, numerous ambulances frequently travel back and forth between the hospital and the industrial area, indicating a hidden reality of ongoing incidents.

National Vital Objects are “a threat to democracy,” says Airlangga, who calls for an independent audit of its status.

According to the Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence (KontraS), an Indonesian rights group, there were a total of 79 reported human rights violations linked to National Strategic Projects in 2019-23. The incidents caused at least 101 injuries, 248 arrests, and 64 cases of psychological violence, including intimidation by authorities.

The actual numbers are likely to be higher because victims are afraid to speak up and limited access to the sites makes it difficult for journalists to report the cases.

Muhammad Isnur, chairperson of the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI), is skeptical the government will heed growing calls to audit National Strategic Projects.

He believes that there is currently a lack of political will to protect workers in Indonesia because the central government has interests in prioritizing investments, which conflicts with local governments’ responsibilities to oversee large corporations. “When local officials reprimand a company, central government officials often intervene,” Isnur says.

In the absence of governmental support, labor unions have become the primary avenue for workers to fight for their rights.

However, workers’ rights have significantly been eroded, as successive Indonesian administrations have been pushing policies prioritizing investments and ease of doing business.

As part of its negotiations with the IMF in the late 1990s, Indonesia liberalized labor laws, shifting the responsibility of protecting workers from the government to employees and employers, Isnur says.

He also points out that since Jokowi started the National Strategic Projects in 2016, Jakarta is in charge of licensing and labor supervision in companies like IMIP. Local governments are unable to monitor labor conditions and sanction violations.

The 2020 Omnibus Law, also known as the Job Creation Law, further eroded workers’ protection. Among other things, it makes it easier for companies to terminate employment and bust unions. In contrast, it makes it difficult for workers and activists to lodge a criminal report on labor violations.

The Invisible Struggles

Bombang, a steel production worker at IMIP, tells ERC that supervisors discourage workers from reporting injuries to the company’s clinic, and that workers are often pressured to hide their injuries or lie about them.

“When an incident is reported, the department will come under scrutiny, and the employee may get a warning. Often, the supervisor gets reprimanded,” he says.

IMIP smelter worker Nurdin says that workers are reluctant to report incidents. “They will get a fine and a warning letter, with IDR 500,000 deducted from their salary. They usually also lose production bonuses for six months,” he explains.

If workers fall ill, their salaries will be cut. “They will deduct IDR 100,000. You can receive free medical treatment at the clinic, but your salary and production bonuses are still reduced,” Nurdin says. “I was sick for one day, I just wanted to rest. When I took a day off, they deducted IDR 100,000.”

Despite poor safety protocols and labor rights violations, IMIP’s operations still continue. The workers’ union has requested a halt to activities until proper safety measures are in place, but the company has yet to respond.

Chinese workers familiar with conditions at IMIP have also accused the companies, including the Tsingshan Group, of prohibiting employees from sharing information online and threatening them with fines.

Issues faced by Chinese workers in Indonesia have been largely overlooked due to language barriers. We interviewed Zhang Qiang, a former welder from China’s Henan province, who worked at Delong Industrial Parks’ VDNI (Phase II) in Konawe, Southeast Sulawesi province, and GNI (Phase III) in North Morowali, Central Sulawesi province.

Zhang says he was promised steady work and pay, but his employers withheld his wages and confiscated his passport. “They use your salary as a threat. They tell you that you cannot take a break, and if you do, they will deduct your salary,” he says. “There are no holidays. They just deduct your pay if you don’t go to work.”

He also complains of poor living conditions, with unsafe drinking water, and that he had to buy his own safety gear, which was overpriced.

Medical care was scarce and workers had to pay for treatment themselves. Zhang tried to escape by paying a colleague for a way home, but he was only moved to another work site. Armed guards at the new site restricted his movement.

A Chinese shop owner finally helped him escape, and he flew back to China through Malaysia.

Meanwhile, female workers struggle with health and safety issues at the company. Nyili, a worker at VDNI, tells ERC, “Women don’t get menstrual leave” – although it is guaranteed under Indonesia’s labor law. During her pregnancy, she was denied maternity leave. She still had to work even when she experienced contractions in her ninth month of pregnancy.

IMIP worker Salmah had a similar experience. “Pregnant employees still work the night shift,” she says, adding that workers are allowed maternity leave only after they go into labor. “It’s exhausting.” But, as a single parent, she has no choice but to continue working.

When contacted by ERC, Emilia Bassar, communications director at IMIP, says: “The duration of maternity leave provided is three months: one and half months before childbirth and one and half months after. It can be extended, with the duration adjusted based on a certificate from an obstetrician or midwife.”

Workers also continue to receive full salary during maternity leave, she adds.

Airlangga of AMAR Law Firm says there have been attempts to silence workers and penalize union organizers.

“Communication with victims isn’t easy,” the lawyer says. “There have been efforts to suppress unions.”

Following a labor protest on Aug. 5, 2020, and in the lead-up to a planned strike organized by workers’ union Labor and People’s Alliance, IMIP fired three of the union’s leaders.

IMIP accused them of inciting employees and harming the company by not prioritizing dialogue. The unions demanded the reinstatement of laid-off workers, fair leave policies, an end to union suppression, and opposition to certain company policies, including working conditions and Omnibus Law provisions.

The lack of transparency surrounding these issues further complicates the legal landscape, making it increasingly difficult for workers to advocate for their rights and for lawyers to assist them effectively.

Student activists Christina Rumahlatu and Thomas Madilis were arrested and charged for criminal defamation in August this year, after they took part in a demonstration against nickel mining and industrial operations at IWIP in Halmahera.

Civil society groups continue to demand accountability from the government and nickel companies for environmental damage, disasters, and harm to local communities. They call for an end to environmentally destructive practices in Halmahera.

ERC has contacted the Ministry of Manpower and the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources to ask about criticisms related to OHS, National Strategic Projects and Vital National Objects. However, at the time of publication, responses are not forthcoming.

While the investigation into last year’s IMIP explosions is still ongoing, another explosion occurred on Oct. 25, 2024, at one of its tenants, PT Dexin Steel Indonesia (DSI). The blast killed a worker and injured another.

IMIP acknowledged the incident but said that the wounded worker only sustained minor injuries and that they are investigating the cause.

The incident underscored the ongoing safety issues at nickel smelters in Indonesia. It also raised questions on accountability, whether individual negligence or systemic problems are to blame.

IMIP and other nickel companies operate largely in secrecy. Their designation as National Vital Objects enables them to restrict access to information, avoid independent scrutiny, and prevent journalists from entering the sites.

The global demand for minerals to power green technologies has driven large-scale mining and ore processing operations. But, it has also caused serious concerns about environmental sustainability and poor working conditions. Indonesia’s new President Prabowo Subianto has pledged to continue Jokowi’s policy. That means the local communities – among the world’s poorest and most vulnerable – would continue to bear the brunt, while the workers would keep being treated merely as a cog in the machine.

- Coordinator: Febriana Firdaus (ERC)

- Editors: Febriana Firdaus (ERC), Shuo Miao (Initium)

- Reporters: Febriana Firdaus (ERC), Zulkifli Mangkau (Freelancer), Zhenhua Xu (Initium Media), Eko Rusdianto (Freelancer), Ady Anugerah Pratama (Freelancer), Dedi (Freelancer), Rabul Sawal (Freelancer), Sofyan Siriyu (Mosintuwu Institute), Aditya Putri (Freelancer), Hans Nicholas Jong (Mongabay).

- Researcher: Irsyan Hashim Inding (Freelancer)

- Publishing Editor: Basil Foo (Freelancer)

- Copy Editor: NN (Freelancer)

- Illustrator: Amin Landak (Malaysiakini)

- Data visual: Ooi Choon Nam (Malaysiakini)