- Not a ‘silver bullet’

- Surging demand for transition minerals

- Hyperfixation to meet ambitious targets

- Uncovering greed behind green targets

- Argentina: ‘Divide and conquer’

- Congo: Women’s reproductive health in world’s copper capital

- Indonesia: Jokowi’s green paradox

- Guideposts to a ‘just’ transition

Global mining

firms turn

communities into

‘sacrifice zones’

to power green

energy

Global mining firms turn

communities into

‘sacrifice zones’

to power green

energy

This story was produced by the Environmental Reporting Collective in partnership with Initium Media, Mongabay Africa, Mongabay Latin America, The Investigative Desk, and The Reporter.

Published on Nov 18, 2024

Argentina’s Puna region is known for its natural wonders. Rivers and streams form an ecosystem that nourishes a wetland about 3,300 meters above sea level.

The high-altitude biome extends across the Andes mountain range in South America where three species of flamingo, suris, and the camel-like vicuña call home, along with grazing animals that communities there raise for their survival.

This region contains lithium deposits that are attracting interest from energy companies including Tecpetrol. Lithium, a chemical element used in batteries for electric vehicles and mobile devices, is becoming increasingly sought after in the Puna region.

The company, owned by the Italian-Argentine multinational Techint Group, has set its sights on the Guayatayoc Lagoon, an area where the prospect of mining seemed inconceivable – until now.

Tecpetrol’s activities in the Puna region are part of a broader trend in Argentina and several countries in the Global South, where exploration and large-scale mining have intensified due to the global demand for minerals needed to power green technologies.

However, these developments are raising serious concerns about sustainability, as multinational mining companies exploit the world’s poorest and most vulnerable communities, extracting resources that developed nations need.

This is underscored in “Greed of Green,” the latest investigation by the Environmental Reporting Collective (ERC) spanning three continents.

From smelting factories in nickel-rich Indonesia to the copper belt region in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 40 journalists in 11 countries uncover the punishing human and environmental cost of the global shift to renewable energy. Since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2016 – a treaty adopted by 196 countries to combat climate change – governments have ramped up investments to achieve “net zero” emissions. This means any greenhouse gas emitted must be balanced by removing an equivalent amount, with the goal of halting further increases in global temperatures.

Over the past decade, we have witnessed the rise of clean energy technologies, such as electric vehicles, solar panels, wind turbines, and battery storage systems – to meet this target.

This climate goal relies heavily on a diverse range of the so-called “critical transition minerals and metals”, such as nickel, cobalt, copper, and lithium, which are predominantly found in Global South countries.

This transition, from producing energy using sources that release greenhouse gases, like fossil fuels, to those that release little to no greenhouse gases, aims to benefit everyone by enhancing economic opportunities in resource-rich nations and reducing carbon footprint globally.

However, the extractivist nature of this process, often occurring under poorly regulated regimes, has instead heightened vulnerabilities and intensified inequalities in regions such as Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and South America.

Not a ‘silver bullet’

Seb Muñoz, senior programs officer at the U.K.-based War on Want, says the energy transition occurring in the Global North should take into account how the Global South is impacted.

Muñoz points out this is because those who have done the most to cause the climate crisis should prioritise taking responsibility for it.

“So it (energy transition) doesn’t become a question of security, a question of competition, a question of a race to the bottom. Instead, it becomes a question of cooperation that we need to address the climate crisis.

“That’s primarily so that we don’t turn the Global South into a ‘sacrifice zone’ to meet the transition of the North,” Muñoz says.

Marvin Lagonera, Forum for the Future’s energy transition strategist in Southeast Asia, says while it is important to achieve those ambitious targets, what received less attention are the environmental and social impacts of the renewable energy transition.

“There’s a notion that renewable energy is a silver bullet and that it’s inherently good. However, there needs to be more of a critical lens to the transition to really be able to understand the various social and environmental impacts across the value chain,” he says.

Surging demand for transition minerals

The production of transition minerals and metals has surged since the signing of the Paris Agreement.

In countries like Argentina, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Indonesia, which hold some of the largest reserves of these resources, output has increased by up to sevenfold over the past decade.

The extensive mining of these materials is accompanied by conflict in land use and struggle for gains, often leaving those with the least power at the bottom.

For instance, War on Want conducted one of the first comprehensive documentation of abuses associated with the extraction of transition minerals, starting with the expansion of nickel mines in Southeast Asia.

Separately, the Global Environmental Justice Atlas has compiled at least 788 cases of social and environmental conflicts related to the mining of mineral ores and building materials. More than 270 of these cases are related to the extraction of minerals and metals needed for energy transition.

The situation is projected to worsen ever more, with demand for these resources expected to surge by over 1,500% by 2050, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Still, the UN agency found that current production levels would fall short of what is needed to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. This is anticipated to further accelerate the need for critical minerals.

Already, UNCTAD has identified 110 new mining projects globally, with USD 22 billion invested in 60 projects located in developing countries.

But to meet the 2030 net-zero emissions targets, the industry is projected to require approximately 80 new copper mines, 70 new lithium mines, 70 new nickel mines, and 30 new cobalt mines.

Hyperfixation to meet ambitious targets

Lagonera points out that the UN Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai last year achieved a significant milestone, with nearly 200 countries making major collective pledges on energy in line with Paris Agreement targets.

However, a report released by the International Energy Agency (IEA) showed that countries are far from meeting that objective.

Of the 194 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) previously submitted, only 14 include explicit targets for total renewable power capacity.

NDCs are plans developed and prepared by countries, which they submit to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Renewable capacity ambitions by 2030 across NDCs only come up to over 1,300 gigawatts or just 12% of the global tripling pledge, which requires at least 11,000 gigawatts by 2030.

The IEA report also found that over 90% of that target from all NDCs comes from China’s goal of 1,200 gigawatts of solar and wind energy.

Lagonera says that there’s a lot of work that needs to be done with this hyperfixation on technical aspects of the transition to meet ambitious renewable energy targets globally. He noted complexities present in the supply and value chains.

He highlights that mineral extraction is only one part of the value chain, which already has a lot of underreported social and environmental implications.

Beyond resource extraction, he says there are other parts of the value chain like site planning for solar and wind farms, which might also impact terrestrial and marine biodiversity.

“That means there are social and environmental risks throughout the value chain like when you talk about mineral extraction or even actual site planning and construction (for solar and wind farms as examples), there are social and environmental risks.

“Some parts of the landscape, the natural landscape will be compromised,” Lagonera says.

Uncovering greed behind green targets

ERC’s latest reporting project, “Greed of Green,” spanning three continents, reveals how the mining industry has capitalized on the rising demand for these critical resources.

Our investigations indicate that mining operations by Tecpetrol in Argentina, Musonoïe Mining Company in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Tshingshan in Indonesia have raised environmental and community impact concerns amid questions about regulatory oversight in these regions.

Here are highlights from our partners’ coverage in Argentina, the DRC, and Indonesia.

Argentina: ‘Divide and conquer’

In Argentina, Tecpetrol has recently entered Rinconadillas, a rural village in Jujuy province, where just a few months prior, the prospect of lithium mining seemed unimaginable.

For over 14 years, 38 indigenous communities here have actively resisted mining operations to protect their land and way of life.

Reporters from conservation news site Mongabay, Emilia Delfino and David Correa, discovered how the company tore apart a community of 82 families and obtained the social license to extract the coveted “white gold.”

Sources describe an “extraordinary” assembly that was called by town authorities of Rinconadillas to be held on June 21, 2024, five weeks ahead of schedule.

The invitation to the assembly was made just two days before and excluded neighbors who do not live in Rinconadillas. Typically, notices are given one week in advance, and residents from neighboring areas are also consulted.

Out of a total of 82 families who registered, only representatives from 51 families came to vote, a sufficient number for the assembly to take place. Of the 51 representatives, 29 voted in favor of granting Tecpetrol the social license while 22 opposed.

A source says several presentations were made during the assembly but the majority were in favor of giving Tecpetrol the go-ahead. After two hours, it became clear that there would be no consensus, so the vote was taken by a show of hands.

“Unfortunately, we were beaten,” says an assembly member who was consulted.

With promises of work and the provision of basic services, the oil and gas giant managed to enter the most conflictive area for lithium mining in Argentina.

Melisa Argento, a researcher at the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (Conicet), says the promise of employment may be valid at first because companies are in the construction phase and can hire local labor.

But when the work becomes more technical, they lay off workers resulting in unemployment in the region.

“Mining companies and corporations know very well that the strategy is ‘divide and conquer,’” she says.

Argento adds it is a matter of dividing the communities into “winners” and “losers,” where the winning communities are those who will receive benefits from mining companies.

“The others are the relegated ones, the forgotten ones, whose territory is also destroyed, their way of life, their agriculture, their pasture, their animals die, they have territorial conflicts all the time with the companies,” she says.

Congo: Women’s reproductive health in world’s copper capital

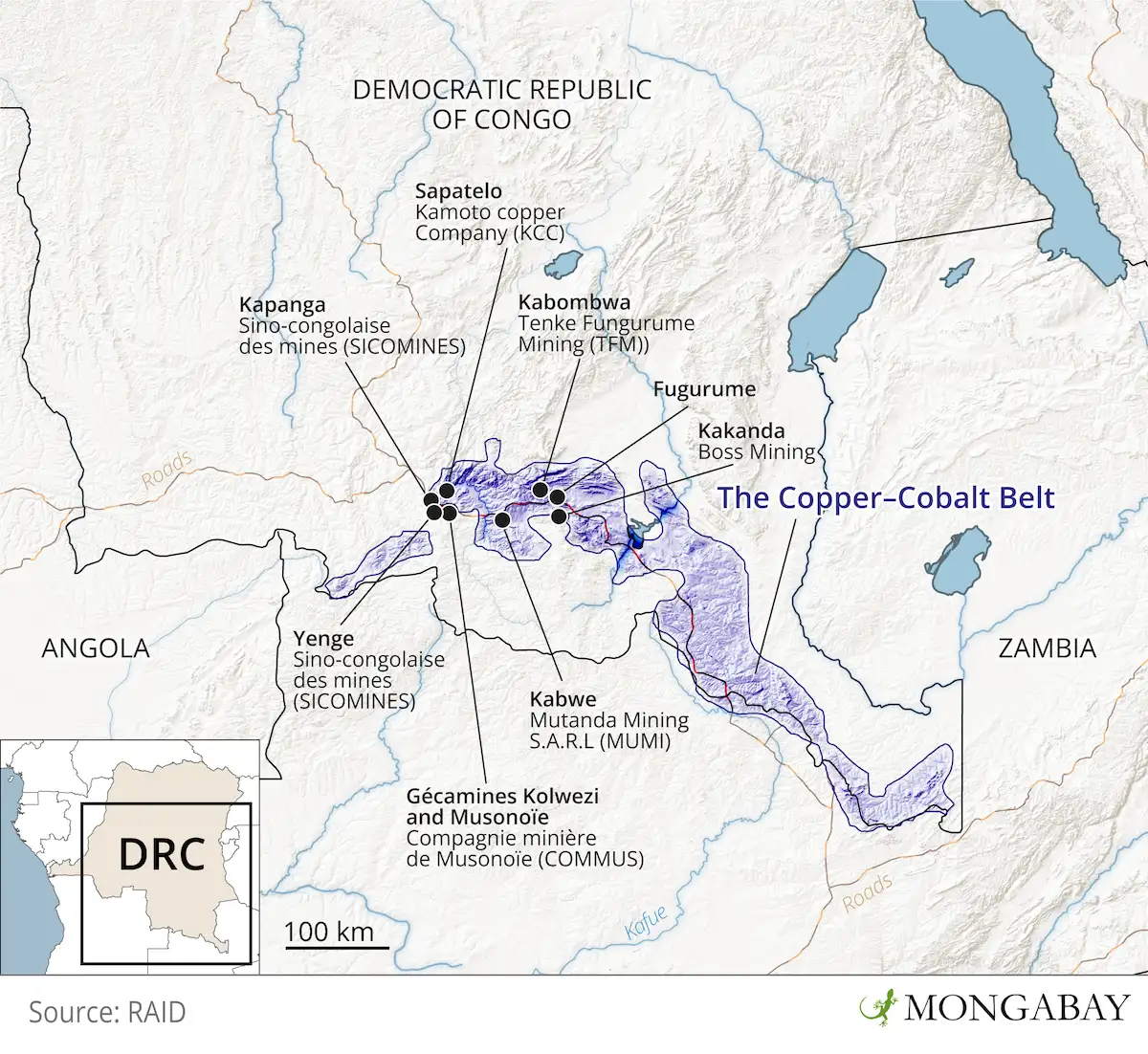

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in Central Africa produces over 60% of the world’s cobalt, used in rechargeable batteries, electric cars, mobile networks, and mobile devices.

In May 2024, Mongabay released a series of reports on the impacts of cobalt and copper mining in the DRC.

Leading the investigation, Pulitzer Center fellow Didier Makal visited several villages to document the environmental and social risks tied to mining.

Makal documented how mining-related pollution has led to deaths, infant health issues, crop destruction, water contamination, and the displacement of entire villages – all while companies neglect their legal responsibilities to address these issues.

In Kolwezi, in the south of the DRC, Makal and fellow journalist Denise Maheho probed the impact of mineral extraction on reproductive health. This particularly affects women whose income comes partly from artisanal mining, using basic tools to extract gold, gemstones, and precious metals from the ground.

Here, the Compagnie Minière Musonoïe (COMMUS), a subsidiary of the Chinese multinational company Zijin Mining group, is operating an open-pit mine and processing plant to produce copper ingots and cobalt.

Residents have reported a troubling increase in birth defects, stillbirths, and infant deaths.

It is clear that the health of women miners is affected by inadequate hygiene, stemming from limited access to clean drinking water and sanitation, which increases the risk of infections and gynecological problems.

To investigate further, Mongabay looked into the experience of artisanal miners extracting copper and cobalt from COMMUS’ mining residues.

In Kapata, just a 20-minute drive from Kolwezi, women spend eight to 10 hours daily cleaning unearthed ores. They work barefoot in contaminated water, handling the black stones with little awareness of the potential radiation hazards.

Scientists, including Queenter Osoro from Kenya’s Nuclear Power and Energy Agency, warn that certain rocks may contain high radiation levels due to small amounts of uranium and thorium. These elements decay into highly radioactive materials.

Radiation contamination can spread into rivers, putting refinery workers at risk from residues that may contain radium, a toxic element produced from uranium decay.

This case is known to the Lualaba provincial authorities and the environmental administration. When contacted about these accusations, the head of the Mining Environment Office at the Provincial Mining Division gave assurance that his department was working on the matter.

In the DRC, the law is clear. If mining activities take place within 500 m of residences, the exposed population must be relocated. However, the issue lies in the law’s implementation and follow-up.

In April 2024, the DRC government suspended production at the COMMUS mine due to concerns about elevated radioactivity in the extracted ores. This suspension was lifted less than a month later.

Mongabay reached out to COMMUS and Zijin Mining over pollution accusations and the mine’s proximity to homes. Both have not responded as of press time.

Click here to read Mongabay’s story in full.

Indonesia: Jokowi’s green paradox

A similar story unfolds in Indonesia. Here, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has ambitious goals for the country’s nickel industry.

By developing its own nickel processing plants and a homegrown electric vehicle market, Jokowi sought to escape the “resource curse” that has plagued many resource-rich nations.

Indonesia imposed a ban on nickel ore exports in 2020 and incentivized the local processing industry with tax breaks.

Chinese firms largely control Indonesia's nickel industry, with billionaire tycoon Xiang Guangda at the helm. With support from China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Xiang’s company Tsingshan partnered with Indonesian firms to build the Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP), now the country’s largest nickel-processing hub.

Tsingshan, headquartered in Argentina, has lithium projects in the South American country, producing enough of the chemical to manufacture batteries for some 600,000 vehicles per year.

Meanwhile, IMIP, in Indonesia’s Central Sulawesi province, is a death trap. Journalists Febriana Firdaus, Zulkifli Mangkau, Eko Rusdianto, Ady Anugerah Pratama, Rabul Sawal, and Sofyan Siriyu interviewed dozens of workers in Morowali to uncover the story behind a series of explosions onsite.

A database built by the ERC from medical records reveals the harrowing plight of both Indonesian and Chinese workers.

In 2023 alone, at least 333 patients were transported by IMIP ambulances to the Morowali Regional General Hospital, highlighting severe health risks tied to unsafe working conditions.

The workers who were treated mostly suffered from bone fractures, burn injuries, and respiratory infections.

Workers in IMIP are not alone. Workers in other smelters in Sulawesi and Maluku have reported 101 deaths, 240 injuries and nine suicides across the metal mining industry, according to watchdog Trend Asia.

Jokowi’s bold vision remains unfulfilled, while those on the frontline experience the grim realities of working in the world’s largest nickel industrial zone – a critical supplier to electric vehicle manufacturers worldwide.

It underscores the human cost of the green tech boom, where safety measures and worker protection often fall short. Click here to read the Indonesia story in full.

Guideposts to a ‘just’ transition

As governments, energy developers, regulators, and financial institutions push for decarbonization efforts, the road to renewable energy must not be done at the expense of the poor and marginalized, as well as future generations.

A shift to renewable energy is necessary, but there are many ways in which that shift could play out.

Lagonera emphasizes the complexities of achieving the Paris Agreement targets as the renewable energy transition also involves social and environmental risks. “We want to first identify those risks, confront those tensions, and be able to come up with ways to manage those risks,” he says.

From his extensive work with the Responsible Energy Initiative, Lagonera points to two key mechanisms: the Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) and the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) processes.

The FPIC, he explains, can often be viewed as a checklist or a procedural requirement, rather than an opportunity for inclusive engagement with communities.

The EIA, he says, is meant to be comprehensive, ensuring that consultations with the community are also embedded. Oftentimes, these assessments are bypassed or are not done with the level of detail needed to actually mitigate risks.

Speaking broadly, Muñoz of War on Want says the problem is viewed simply as a question of decarbonization and not transitioning economies towards more sustainable systems.

“The transition cannot just be about switching from fossil fuels to renewable energies. It needs to be about recognizing the relational – societal, economic, and ecological – systems that need to transition as well,” he says.

“So it’s not just decarbonization, it’s a social and ecological transition.”

This story was produced by the Environmental Reporting Collective in partnership with Initium Media, Mongabay Africa, Mongabay Latin America, The Investigative Desk, and The Reporter.

- Reporters: Emilia Delfino, David Correa, Didier Makal, Denise Maheho, Zulkifli Mangkau, Eko Rusdianto, Ady Anugerah Pratama, Rabul Sawal, Sofyan Siriyu, Febriana Firdaus, and Karol Ilagan

- Photos and videos: Nicolás Núñez, Didier Makal, and Eric Cibamba

- Editors: Alexa Vélez, Latoya Abulu, Basil Foo, and NN

- Visualization: Eduardo Motta, Ooi Choon Nam, and Amin Landak

- Translation: Cait Fahy

- Journalistic coordination: Andrew Ong, Febriana Firdaus, Karol Ilagan, Willie Shubert, Vanessa Romo, and David Tarrazona